|

| Source: CNN |

I was shocked not so much because protestors managed to get the statue down or that I'd never heard of Edward Colston before, but because I knew the name Colston. It was one of my brother in law's paternal family names. They are from Alabama. Take a moment to think about the likely connection. It's sobering.

So I dove back into my BIL's side of the tree again after not working on our genealogy for a couple of weeks. The furthest Colston ancestor I can document thus far is Isaac Colston, born in December 1837. He was my brother in law's great-great-grandfather; my nephew's 3rd great grandfather.

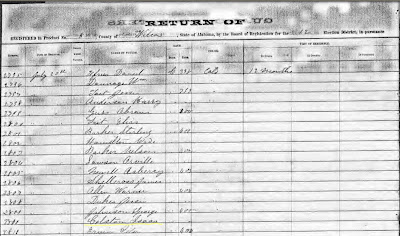

Interestingly, I first find Isaac in the 1867 Alabama voter registry. This registry was created in accordance with the Second Reconstruction Act passed on March 23, 1867. All males above the age of 21 were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the United States and register to vote by September 1, 1867. This registry is one of the first government documents to record the names of black males living in Alabama.

|

| Source: 1867 Alabama Voter Registration |

Isaac married twice - once to an older woman named Priscilla (born between 1820-1823) and second to Margaret Sanders (born about 1845) - and had a total of 10 children (who survived long enough to be counted on the census anyway). In the 1870 and 1880 federal census records, Isaac is living with his family in "Blacks Bluff, Wilcox County, Alabama" and he is listed as a farm laborer.

|

| 1870 Federal Census via Ancestry.com |

I was curious to see where this was. You can find it in what is now known as Coy, Wilcox County, Alabama. The area is currently called Black Bluff and refers to a cliff along the Alabama River. A closer look at the map on Google and I was struck by what was within walking distance.

|

| Black Bluff and its neighbor Dry Fork Plantation |

Dry Fork(s) Plantation is said to be one of the oldest buildings in Wilcox County. It was built between 1832-1834 by two enslaved men named Hezekiah and Elijah for James Asbury Tait. The plantation was documented on March 29, 1936 as part of a Historic American Buildings survey. You can see the entire collection of those pictures on the Library of Congress website.

|

| Cabin? Try slaves' quarters. Source: Library of Congress |

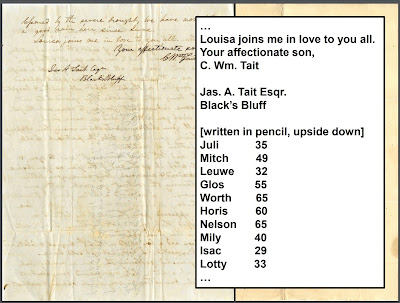

In 1860, Wilcox County had 18,790 enslaved people according to the Federal Census Slave Schedule. There were 524 men between the age of 22 to 23. Isaac Colston was presumably one of them, though it is very difficult to determine where he lived specifically. James Asbury Tait died in 1855. In 1860, his son Robert is listed as owning 148 slaves. There are 3 men in that list of 148 people who were the right age to be Isaac. And then I came across this transcription without a date...

|

| Could this be our Isaac? Source: Auburn University |

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1999, the Dry Fork property is still in possession of one of James Tait's descendants to this day. Here's a write-up in the Wilcox Historical Society newsletter from 2005:

The floor plan specified that the house should have eight rooms with four on each floor. There are two porches on the front, although one appears to be a later addition since James Asbury Tait’s Memoranda does not mention it. All rooms are 18 feet square and with 11-foot ceilings downstairs and 8 ½ foot ceilings upstairs. The original house required more than 25,000 board feet of cut lumber, and the roof was covered with 6,000 wooden shingles. The chimneys required 12,000 bricks, made from clay on the plantation. Gail and James Edwin (Jim) Tait, great-great-grandson of the builder, have beautifully restored the original home just described, and have constructed majestic additions to the original structure. Appurtenances and gardens result in a one-of-a-kind property that one has to see to fully appreciate."

I find it very telling that there's such pride in the story of Tait family and that the two men who built Dry Fork were referred to as carpenters and not slaves. White Americans tend to love glossing over the atrocities of chattel slavery. Don't believe me yet? Well, take a look at the marketing videos the Tait family has created for their plantation.

That's right. Not only do descendants of the original slave owner still own the plantation, but they also host weddings there. Nothing says romance like starting your marriage on grounds where torture, rape and murder were par for the course, amirite? In a somewhat satisfying twist, restorer and great-great-grandson James E. Tait had some shady business dealings and tried to mortgage the plantation to pay off debt, went bankrupt in 2007-2008, the property is technically in possession of other family members now and I can't find a functional website for the wedding business.

So back to our Isaac. A lot of questions still remain to be answered. How did he get the surname Colston? I can't find any white Colstons in Wilcox County as I had originally suspected would be the source of the surname. But I do find Tait plantations (yes, the family had others) in all the hamlets Isaac and his descendants lived. I think the only way to settle it will be to examine the Tait family papers through the Alabama state archive ("Of special interest are the notes beginning in the

back of the volume on slave families, which also notes the year of birth of

children from 1784-1844, and who the parents were"). Next, when did Isaac die? I last find him and Margaret in the 1910 Federal Census, living in Canton with one Anne E. Tait as a neighbor. I don't see either of them in the 1920 census so I suspect they passed away in the intervening 10 years. Where was Isaac buried? I find no older Colston burials listed on Findagrave or Ancestry.com. I also get no results when I search his name on Newspapers.com. These may be questions only solved by actually visiting Alabama or they may not be solvable at all because of a lack of records. Therein lies the rub when you are tracing black American families.

I'm not disheartened though. Yesterday, British citizens took a stand against revering one Colston in order to affirm the value of a whole lot of other Colstons. It gives me hope that plantation weddings and other thoughtless, cruel behaviors that prop up systemic racism will be a thing of the past, at long last.

If you have American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) in your family tree and you want to learn more about how to research your lineage, please check out this helpful guide compiled by Claire Kluskens for the National Archives.

No comments:

Post a Comment